Written by: Noah Smith

Translated by: Block UNI

I actually don't think you can defeat Trump's tariff policy through rational debate or explanation of economic theory. I mean, how do you argue with something like that?

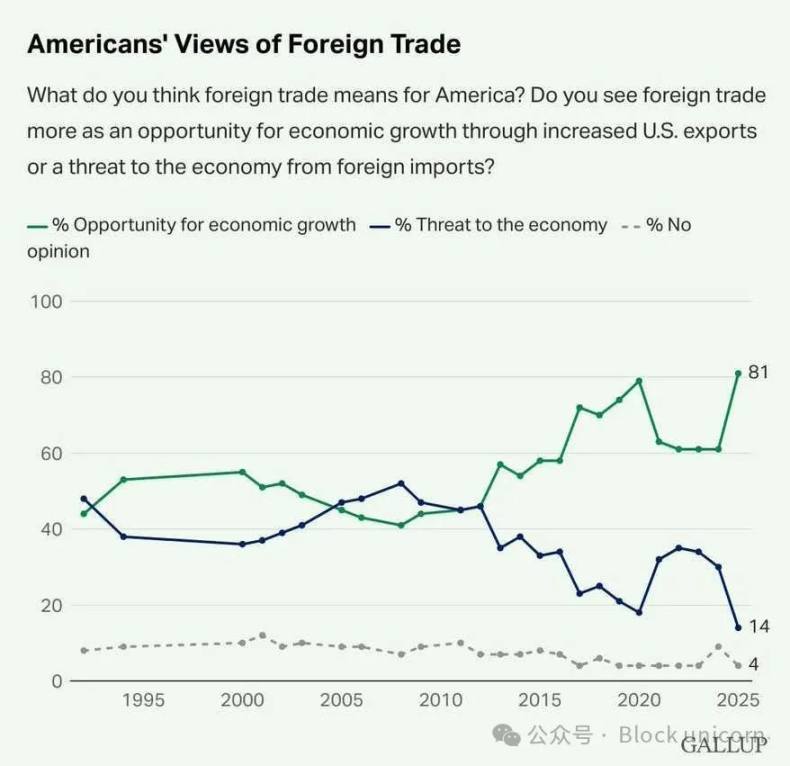

I have accepted an idea that Americans will only become widely aware that broad tariffs are bad by experiencing their negative consequences firsthand - that is, by touching the so-called hot stove. Fortunately, I think Americans may wake up soon:

But anyway, this is an economics blog, so although I don't expect much political return, I want to explain why trade deficits won't make a country poor (though this doesn't mean they don't have problems).

In this situation, we must decide whether "buy now, pay later" is good or bad. Remember, trade deficits are like buying things with a credit card. When the United States imports televisions from China and cars from Canada, and China and Canada acquire U.S. Treasury bonds, it means the United States now owes money to China and Canada.

At any time, China and Canada can choose to sell their bonds to obtain U.S. dollars and then use these dollars to purchase U.S. goods and services. If they ultimately do this, then they will create a trade deficit against the United States. In this case, it is essentially the United States borrowing money from China and Canada and then repaying it.

It's like buying a washing machine from Target with a credit card and then working to earn wages to pay off the credit card. Is this bad or good? It depends on the situation. Perhaps you could wait until you have cash in the bank to buy the washing machine. Or maybe it's worth buying the washing machine now instead of waiting a few months, even if you have to pay a bit of interest on the credit card debt.

Purchasing consumer goods with debt can be a good or bad financial decision. This is basically what the United States does when it has trade deficits with other countries.

It's worth noting that, like credit card borrowers, the United States may never fully repay its foreign loans. If the United States experiences unexpected high inflation, the U.S. bonds held by China and Canada will depreciate. This is essentially like a partial debt default. Or, if an irresponsible U.S. leader appears one day and defaults, China and Canada will see part of the value of their bonds vanish.

Therefore, when the United States has trade deficits with other countries, those countries are actually taking risks. They essentially give us a credit card that we can use to buy things they manufacture. However, there is always the possibility that we might declare bankruptcy and never repay the money.

So it can be said that, in a sense, countries with trade deficits are more focused on the short term, or more impatient, than countries with trade surpluses. Countries do not have motivations and personalities like humans, but thinking about it this way is not too bad.

Will Trade Deficits Deindustrialize the United States?

The final question here is whether importing things from other countries will lead to a reduction in U.S. production. Perhaps if you buy tomatoes with a credit card, you might grow fewer tomatoes in your own garden. By the time you need to repay the credit card debt, you may have forgotten how to grow tomatoes. This is essentially what deindustrialization means.

Obviously, in some cases, trade deficits do not lead to deindustrialization. For example, in the South Korean case of the 1980s and 1990s, we saw that trade deficits helped the country industrialize and improve its manufacturing. Similar things may have happened in the United States in the 1990s.

But okay, we're not talking about those historical cases, are we? We're discussing the trade deficits that have occurred in the United States over the past 25 years, primarily with China, but also including many other countries. These trade deficits are mainly the United States borrowing to consume, rather than invest. The question is whether these deficits have caused the United States to lose manufacturing.

The answer, at least for China, is "definitely". The famous study by Autor et al. (2013) found that "import competition from China explains one-quarter of the total decline in U.S. manufacturing employment during the same period from 1990 to 2007." Bloom et al. (2024) found that Chinese import competition caused massive job shifts from manufacturing to services on the West Coast and in big cities, but in the Midwest, it primarily caused wage declines and unemployment. And Acemoglu et al. (2014) wrote:

In this paper, we explore the impact of the rapid rise of Chinese import competition on slow U.S. employment growth. We find that the increase in U.S. imports from China, which accelerated after 2000, is a major cause of the recent reduction in U.S. manufacturing jobs, and through input-output linkages and other general equilibrium effects, it seems to significantly suppress overall U.S. employment growth... Our core estimates indicate a net job loss of 2 to 2.4 million due to the rise of Chinese import competition between 1999 and 2011. [Emphasis added by me]

You can roughly see this by looking at the original data. Until 2001, when China joined the WTO and began exporting large quantities of cheap goods to the United States, U.S. manufacturing employment had been doing quite well for many years (although the percentage of total employment was declining). In the 21st century—the decade of surging Chinese imports—it was like falling off a cliff:

It's worth noting that it's not the trade deficits themselves that caused these job losses. Even if trade with China were balanced, Chinese import competition might cause some U.S. manufacturing workers to lose their jobs because A) some U.S. exports might be services rather than manufactured goods, and B) the U.S. might export more capital-intensive goods, thus no longer producing labor-intensive products that China was good at producing in the 2000s.

But indeed, the U.S. trade deficit with China is massive and has led to a severe decline in industrialization. Continued U.S. trade deficits with China might hinder U.S. reindustrialization, on one hand due to import competition, and on the other hand because China is squeezing U.S. companies out of export markets.

Therefore, if you believe the importance of manufacturing extends beyond its contribution to GDP (as I do), then trade deficits with China might be an important issue that needs to be addressed.

But this doesn't mean Trump's tariffs are the correct way to solve it! I know I'm repeating what I've written in many other posts, but it's worth repeating. First, Trump's tariffs are weakening U.S. manufacturers by raising the prices of imported components—that's why U.S. auto workers and steel workers are now being laid off, and why manufacturing activity and confidence indicators are declining. Second, Trump's tariffs will ultimately reduce U.S. exports, not just imports, both through exchange rate changes and through retaliation by other countries. This will harm U.S. manufacturing.

Imposing tariffs on China could be part of a larger strategy to improve U.S. manufacturing competitiveness. But broad tariffs on all U.S. trading partners, like Trump just introduced, are likely to accelerate U.S. deindustrialization—even if they also reduce trade deficits. Ultimately, what matters for the United States is not reducing imports, but increasing exports. Trump's tariffs will only harm this goal.